Since a lot of interest in AI alignment has started to build, I’m getting a lot more emails of the form “Hey, how can I get into this hot new field?”. This is great. In the past I was getting so few messages like this that I could respond to basically all of them with many hours of personal conversation.

But now I can’t respond to everybody anymore, so I have a new plan: leverage academia.

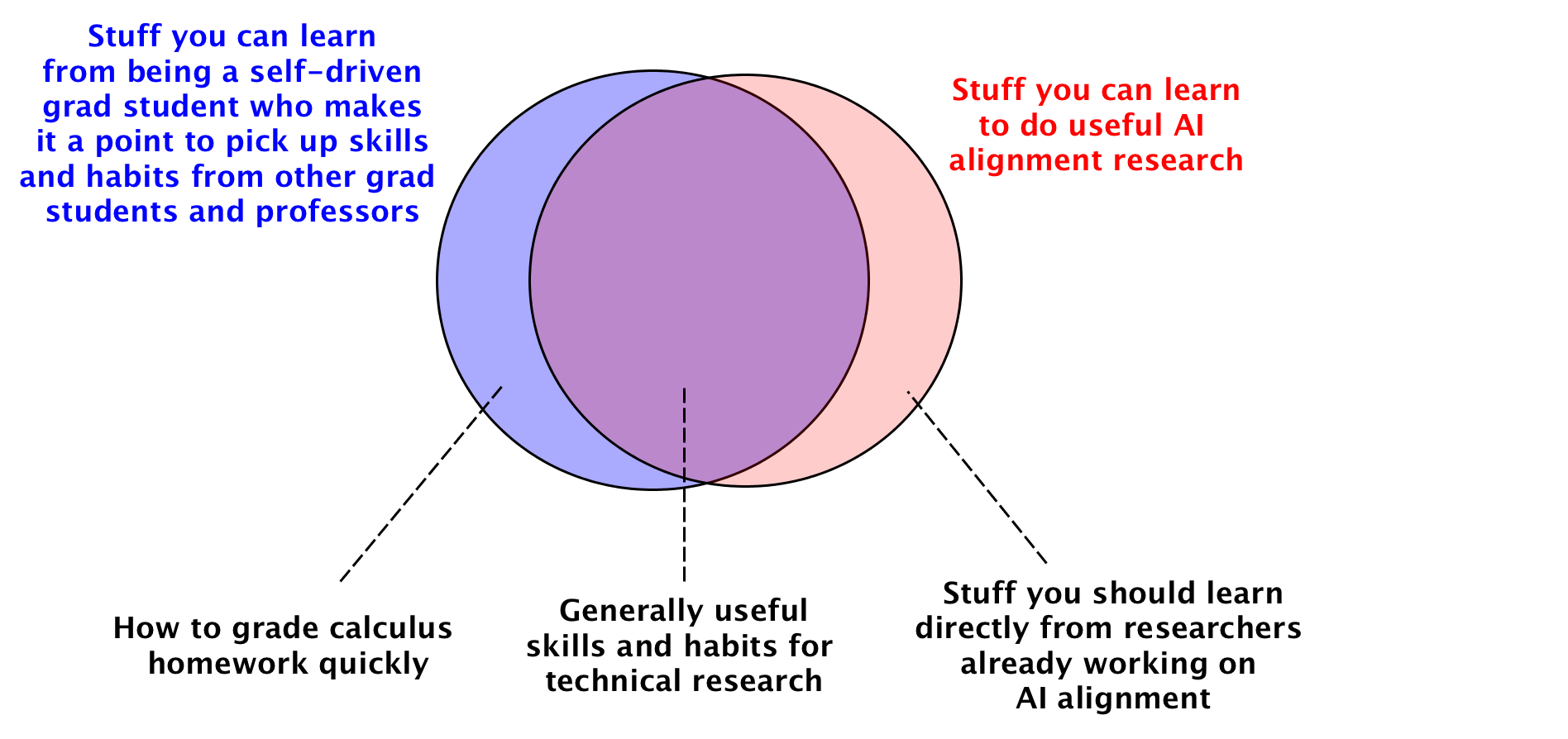

To grossly oversimplify things, here’s the heuristic. If the typical prospective researcher (say, an inbound grad student at a top school) needs 100 hours of guidance/mentorship to become a productive contributor to AI alignment research, maybe only 10 of those hours need to come from someone already in the field, and the remaining 90 hours can come from other researchers in CS/ML/math/econ/neuro/cogsci. So if I have 100 hours of guidance to give this year, I can choose between mentoring 1 person, or 10 people who are getting 90% of their guidance elsewhere. The latter produces more researchers, and potentially researchers of a higher quality because of the diversity of views they’re seeing (provided the student has the filter-out-incorrect-views property, which is of course critical). So that’s what I’m doing, and this blog post is my generic response to questions about how to get into AI alignment research 🙂

I think this policy might also be a good filter for good-team-players, in the following sense: When you’re part of a team, it’s quite helpful if you can leverage resources outside your team to solve the team’s problems without having to draw heavily on the team’s internal resources. Thus, if you want to be part of a new/young field like AI alignment, it’s nice if you can draw on resources outside that field to make it stronger.

So! If I send you a link to this blog post, please don’t read me as saying “I don’t have any advice for you.” Because I do have some advice: aside from going to grad school and deliberately learning from it, and choosing Berkeley for your PhD/postdoc (or transferring there), I’m also advising that you acquire and demonstrate the quality of drawing from non-scarce resources to help produce scarce ones. Use non-scarce resources to decide what to learn (e.g., read this blog post by Jan Leike); use non-scarce resources to learn that stuff (e.g., college courses, online lectures, books), and use non-scarce resources to demonstrate what you’ve learned (standardized tests, competitions, publications), at least up to the point where you get admitted as a grad student to a top school. And if that school is Berkeley, I will help you find an advisor!